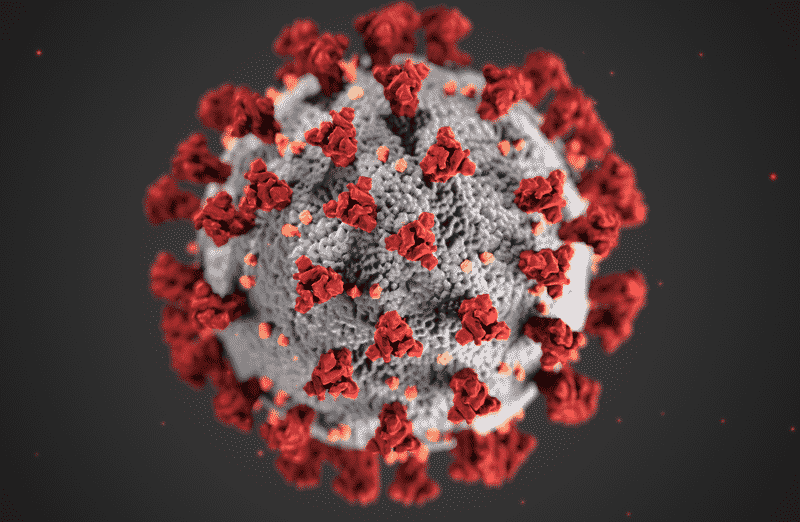

College students’ return to campus in the fall of 2020 has been a popular news item. At a number of schools, students have been disciplined, and in some cases, expelled, for violating rules requiring social distancing and prohibiting large gatherings. Coronavirus infections on campus have been traced to parties, social gatherings, and the fact that students and employees of colleges are all in close proximity. Shockingly, recent news has revealed that universities are withholding news of coronavirus infections on campus. In some instances, faculty members have been threatened with serious job consequences if they share news of infections. Some universities have claimed, inaccurately, that the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) requires this silence.

How Have Colleges Responded to Coronavirus Infections

A number of major universities appear to be deliberately violating HIPAA, in an effort to conceal the presence of coronavirus infections on campus.

At the University of Alabama, department leaders have threatened faculty members with “serious consequences” if they shared news of coronavirus infections on campus. Arizona State University, another public school, only revealed its coronavirus infections case count after a court ordered it to – after its president refused to do so. At a third public school, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, administrators told the student newspaper that the school would not reveal the number of coronavirus infections.

Michael Innis-Jiménez, an American history and labor studies professor at the University of Alabama stated, “We’re really nervous, anxious and scared. It’s a big mystery exactly how [the virus] is going to get you if it’s going to get you. People are really worried about that, and to be forced to keep your job, and be in that position — and you’re willing to be in that position — and be told that ‘we’re going to keep it a secret if you were in the same room as somebody.”

These schools’ rationale for this obstruction is that the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), a federal law protecting student education record privacy, justify the secrecy. This law may be used to prevent disclosure of protected health information of individual students. The schools are not merely withholding this information. The schools are withholding overall coronavirus campus data, such as infection rates.

The agency that administers FERPA has already told schools that they are wrong in adopting this approach. Back in March of 2020, the Department of Education released FERPA guidelines, which stressed that schools could share coronavirus data so long as personal student information was not shared.

At the same time, the Department of Education stated that sharing coronavirus numbers without revealing student personal information was justified under FERPA’s “emergency exception” to the non-disclosure of student data. An example of an emergency justifying disclosure is the outbreak of an epidemic disease. Schools may violate FERPA when a professor states, “student John Smith has coronavirus.” However, if a professor simply states, “A student in this class has tested positive for coronavirus,” there has been no FERPA violation. The stated goal of Congress in passing FERPA was to provide for privacy of student educational records – not to keep parents and students in the dark about public health emergencies.

Public schools’ efforts to silence students, professors, and newspapers from lawfully reporting coronavirus infections information also raise First Amendment concerns. Under the First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press from the government, public universities are considered to be government entities.

Regarding HIPAA laws and COVID, universities have also claimed, improbably, that HIPAA requires that they keep information about coronavirus a secret. However, HIPAA applies only to covered entities (healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses) and business associates. By definition, public schools and universities are exempt from HIPAA’s requirements.

This would come as news, sadly, to the University of Alabama. The same week that the school racked up 1,368 total coronavirus infections, a prominent newspaper obtained an email from the school to the English Department. The email, obtained by The Post, had advised the English department faculty to “NEVER, EVER refer to, mention, or discuss student health.” The email further advised, inaccurately, “This injunction extends to what some might consider an anonymized statement like, ‘Two students in my class tested positive.’ Even if this seems like an innocuous statement, it is not. In the current environment, people can make deductions, making ANY reference to student health a potential HIPAA violation.” Not only did the school incorrectly cite HIPAA as a reason for what was effectively a gag order on its faculty; it cited a provision of HIPAA that does not even exist.

Threatening emails like this one, and threats that faculty will face serious consequences, have left instructors in fear of violating laws that are not even applicable to them. FERPA, for example, only apples to school records – as in paper or electronic information – and not to verbal disclosures. Since colleges have no legal basis for silencing their own employees, it remains to be seen why colleges are so intent on stifling discussion of coronavirus infections. Then again, there has been a long historical practice of universities crying “FERPA!” in denying requests for information FERPA says absolutely nothing about.