The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office for Civil Rights enforces HIPAA compliance by imposing civil monetary penalties (CMPs) on HIPAA covered entities for violations of the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules. Practices may appeal the monetary determination in civil court. Almost all appeals to date have been unsuccessful. Almost. On January 14, 2021, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (“5th Circuit”) vacated, or set aside, a $4.3 million CMP imposed by OCR in 2017 on provider M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. M.D. Anderson is part of the University of Texas health system. The 5th Circuit found that OCR’s decision was arbitrary and capricious, meaning the decision lacked a valid legal basis. The 5th Circuit case, and what it means to providers and business associates, is discussed below.

Reading the 5th: The Facts

In 2017, OCR issued its $4.3 million CMP on two grounds: 1) M.D. Anderson allegedly improperly disclosed PHI, in violation of the HIPAA Privacy Rule; 2) M.D. Anderson failed to implement a mechanism to encrypt ePHI, in violation of the HIPAA Security Rule. The OCR’s penalty was affirmed by an HHS administrative law judge. M.D. Anderson appealed the judge’s decision. The 5th Circuit then reviewed the decision anew, reversing the judge’s decision.

The facts of the 5th Circuit HIPAA case are fairly simple. First, an M.D. Anderson faculty member’s laptop was stolen in 2012. The laptop was not encrypted or password-protected, but it did contain “electronic protected health information (ePHI) for 29,021 individuals.” Second, also in 2012, an M.D. Anderson trainee lost an unencrypted USB thumb drive during her evening commute. That thumb drive contained ePHI for over 2,000 individuals. Finally, in 2013, a visiting researcher at M.D. Anderson misplaced another unencrypted USB thumb drive, this time containing ePHI for nearly 3,600 individuals. From these facts, HHS concluded that M.D. Anderson failed to properly encrypt ePHI, and impermissibly disclosed it.

Reading the Fifth: The Law

In the 5th Circuit HIPAA case, the 5th Circuit rejected OCR’s conclusion that MD Anderson had failed to implement a mechanism to encrypt ePHI. M.D. Anderson had implemented several mechanisms to encrypt ePHI, including an “IronKey” for mobile device encryption and decryption, as well as a mechanism to encrypt emails. By doing so, the 5th Circuit held, M.D. Anderson satisfied the only legal requirement at issue: the requirement to implement a mechanism to encrypt PHI.

The judge, the 5th Circuit held, erred in finding that the Encryption Rule required more than what the plain text of the rule required. The rule simply requires that a covered entity or business associate implement a mechanism to encrypt ePHI. The judge interpreted the rule to mean that covered entities were required to assure that “All systems containing ePHI be inaccessible to unauthorized users.” In other words, the judge invented a requirement under which not only must a covered entity implement a mechanism for encryption – the mechanism must be foolproof. And, if it is not, the judge reasoned, HIPAA has been violated. The 5th Circuit rejected the judge’s reasoning, finding that the encryption “failure” by M.D. Anderson was that three employees failed to abide by the encryption mechanism, or that the mechanism was not rigorously enforced. (M.D. Anderson might have done a better job of training its workers on how to secure mobile devices from theft, though). Since, though, all that was required was for M.D. Anderson to HAVE a mechanism, which it did, there was no HIPAA violation.

The Fifth Circuit likewise rejected the judge’s conclusion that MD Anderson committed a Privacy Rule violation. The Privacy Rule, as relevant to this case, prohibits a covered entity from “disclosing” PHI. The rule defines disclosure as “the release, transfer, provision of access to, or divulging in any manner of information outside the entity holding the information.”

The judge concluded that what this means is that a covered entity violates the “Disclosure Rule” whenever it releases (i.e., loses control of, which is what happened in this case), irrespective of whether anyone outside the covered entity actually accesses it. The 5th Circuit found this reasoning to be flawed. However, it is undisputed that no one outside of M.D. Anderson actually viewed or accessed the information. Therefore, the 5th Circuit held, since “disclosure” requires information end up in the hands of someone outside of the provider, and that this did not happen, there was no impermissible disclosure, and M.D. Anderson did therefore not violate the Privacy Rule.

The 5th Circuit also agreed with M.D. Anderson that the judge’s selectively disciplining it was against the law. At the hearing before the judge, and before the 5th Circuit, M.D. Anderson gave examples of other covered entities that violated the Government’s understanding of the Encryption Rule, and faced zero financial penalties. One example of an entity being let off the hook was when a Cedars-Sinai employee lost an unencrypted laptop containing ePHI for more than 33,000 patients in a burglary. HHS investigated and imposed no penalty at all. The government feebly attempted to reject the contention that it was treating cases differently, stating that it “evaluates each case on its individual facts.” However, since the facts of these two cases were very much similar, and the government nonetheless imposed a $4.3 million penalty in one case and a penalty of zero in another, HHS was required to explain why the two cases were decided differently – what it was that set them apart to the tune of $4.3 million.

Failing to treat like cases alike raises significant problems. First, imposing wildly different penalties for no rational reason raises significant concerns about equal protection of the law. Beyond that, the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of due process requires that individuals and entities know what conduct is prohibited, so they can conform their actions to the law. HHS, by rewriting the regulation, “made up” illegal conduct, at M.D. Anderson’s expense. As the Fifth Circuit noted, HHS had the option to define the regulations to mean what the judge believed they meant. This option, though, can only be exercised through formal rulemaking – through a process of publicly issuing a proposed rule change, inviting the public to comment on it, and then rationally implementing the change.

Finally, the Fifth Circuit held that the amount of the CMP exceeded the maximum fine permitted by Congress. What particularly drew the Fifth Circuit’s ire was that the judge not only ignored Congress’ established fine limits, but that HHS also ignored its own regulations regarding severity of penalties. Those regulations require HHS to consider the following factors (among others) in assessing a CMP: (1) Whether the violation caused physical harm; (2) Whether the violation resulted in financial harm; (3) Whether the violation resulted in harm to an individual’s reputation; and (4) Whether the violation hindered an individual’s ability to obtain healthcare. Suffice it to say, HHS did not perform this analysis, let alone prove physical, financial, or reputational harm, or prove that someone’s ability to obtain healthcare had been hindered.

Reading the 5th: The Analysis

Is the 5th Circuit HIPAA case decision now the law of the land? Is OCR now prohibited from issuing fines? Is encryption unnecessary? The answer to the second question and third questions are a clear “no.” (The importance of encryption is well-described here, here, and here. The Security Rule does not allow for use of any “encryption mechanism” – An effective encryption mechanism is called for). The 5th Circuit HIPAA case decision held that OCR may only issue fines when a rule that exists on paper – as law – is broken, not when a rule that exists only in a judge’s head is broken. As to whether the decision is the “law of the land,” yes….and no. The Fifth Circuit is the federal circuit court of appeals presiding over Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Prospectively, entities in those states may, if fined by OCR using any of the flawed rationales above, appeal to the 5th Circuit. The 5th Circuit (and any lower courts from which a litigant can appeal to it in Mississippi, Texas, or Louisiana), if inclined to follow its own precedent, may reach the same decision.

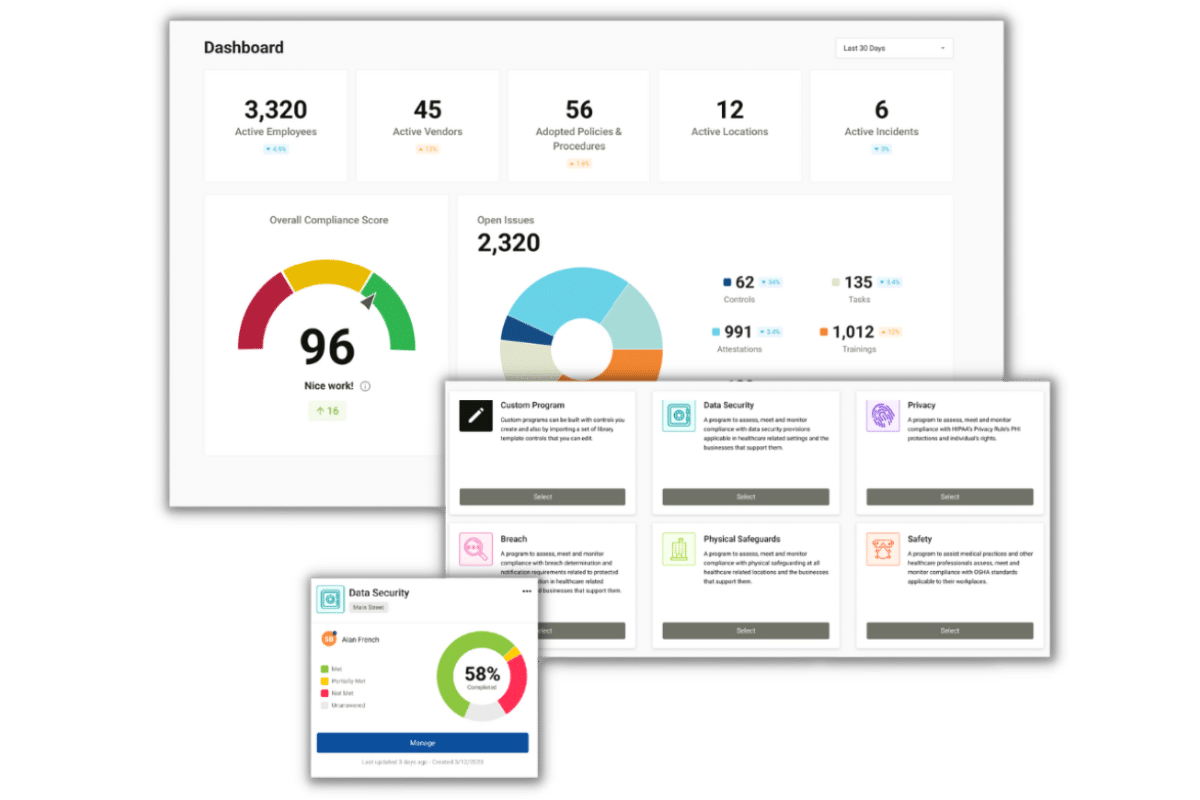

The significance of the decision on a practical level is in the lesson the decision (whether its logic is dubious or not) teaches: HIPAA regulations are not black and white. The regulations are nuanced. There are shades of gray. Even HHS can misinterpret its own law. Covered entities and business associates who try to “go it alone” and interpret for themselves what the rules mean, or who use a de-personalized checkbox solution that does not even recognize the difference between a covered entity and a business associate, do so at their legal peril. A covered entity or business associate that works with a third-party compliance tracking solution, such as Compliancy Group, that can explain not only what the law says but what it actually means and what it actually does and does not require you to do, will save time and money (potentially in the tens of thousands).

Compliancy Group’s Compliance Coaches guide clients through the process of implementing an effective HIPAA compliance program. We understand that HIPAA law can be confusing – as evident by the M.D. Anderson case – which is why we provide you with live coaching and support. Our Coaches take it a step further by verifying and validating that clients have everything they need in place to prove their “good faith” effort towards compliance should they be subject to a HIPAA audit. We know not only the law, but how it has been interpreted, and how it actually applies to you. You can decide something much simpler than what the 5th Circuit was asked to – to partner with us.

Reading the 5th: A Flawed Decision?

The decision is not binding on any other federal circuit court of appeals (there are 12 circuit courts throughout the U.S. that can hear this type of case). If other appeals courts find the rationale of the 5th Circuit HIPAA case decision to be persuasive, these courts may issue decisions about encryption and disclosure using similar reasoning – but, they are not required to.

Indeed, the reasoning employed by the 5th Circuit has already been the subject of ridicule by legal scholars. A Harvard law blog written eight days after the decision credibly argues that HHS penalized M.D. Anderson not for “having no encryption,” but, rather (and, in the blog’s view, correctly) for not having taken further steps about encryption when it had determined that more was needed in the circumstances in which it operated.

The only way the 5th Circuit HIPAA case decision could become binding on all courts is if that decision were affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. It is extraordinarily unlikely that the Supreme Court would hear to choose this case. In a typical year, the Court is asked to review nearly 10,000 cases, and decides to review around 100 of them – 1%. The cases it does review are ones where the legal dispute is particularly complex, or cases in which different appeals courts have come out differently on the same issue. It stretches the imagination to state that HHS v. M.D. Anderson would be one of these cases.

The ruling is significant nonetheless, because HHS now has a significant incentive to re-write the rules to require that there be effective encryption (as opposed to just implementation of a mechanism for encryption), and to require that a “disclosure” need not involve receipt of information by a third-party. HHS can initiate the rule-making process to start this proverbial ball rolling, at any time.